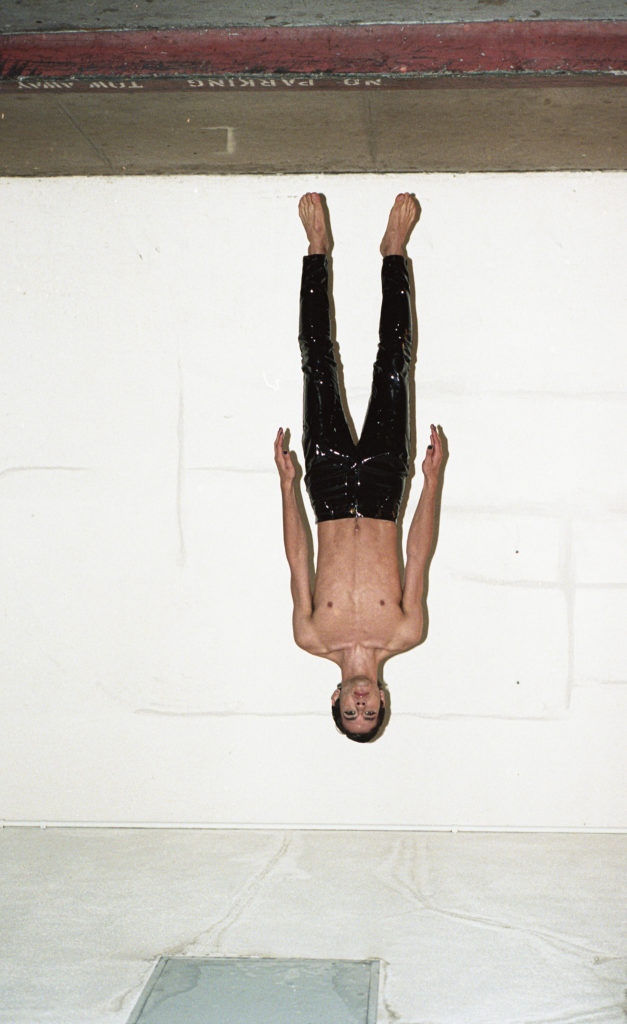

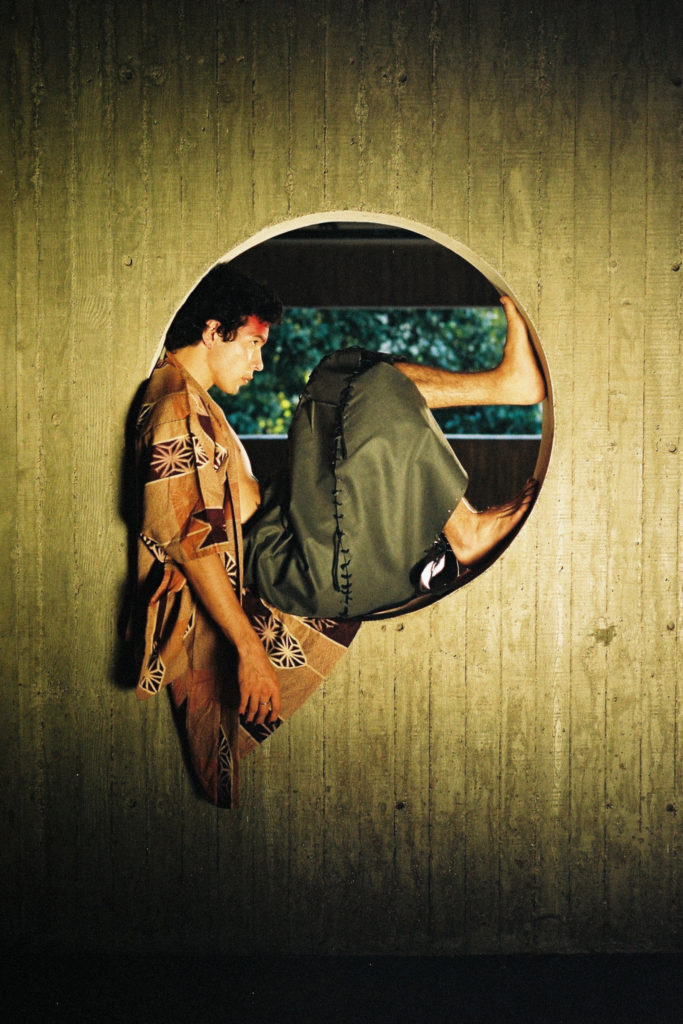

Loud/quiet. Fast/slow. Real/kitsch.

Vincent Bercasio and Jason Chu—two Honolulu-based photographers with contrasting approaches—collaborate on a joint fashion essay where movement, kitsch, and gender clash.

Images by Vincent Bercasio and Jason Chu

Modeled by Madelyn Biven and Nate Sarsona

Clothing by Variable Hawaii

Makeup by Tamiko Hobin

Assisted by Kyle Capacia

VINCENT BERCASIO: Hi, Jason.

JASON CHU: Hey, Vincent. Thanks for meeting me at one of my favorite places in the world: Ala Moana Beach Park.

VINCENT: I’ve actually never been here at night before.

JASON: Really? It’s so magical here at night. I come here a lot at night.

VINCENT: I can see why. Okay, well, let’s jump right in then.

JASON: Let’s do it.

VINCENT: Why do you shoot what you shoot?

JASON: Oh, we are really jumping in! [Laughs] Well, I like to shoot my surroundings to show where I live and the things around me. Nothing terribly insightful there. But when it comes to my portraiture work, however, one of my main aims for a while now has been to capture dynamic body movement.

VINCENT: I remember you would bring up figures like Pina Bausch and Butoh performance when discussing where you draw some of your references from. It’s interesting to see how movement and gesture play a part in your portraits. I feel like the individuals you capture—taken as a whole—could be members of an elaborate stage play.

JASON: I like that comparison. Movement has always been a strong creative element throughout my life. I used to dance hula when I was younger. And I still love dancing at parties—pre-pandemic and hopefully again soon. I’m definitely drawn to the drama of Bausch’s work and of Butoh. I think you can see those influences in a lot of my work.

JASON: As for you, you mentioned to me earlier that you don’t really shoot a lot of portraiture. As far as our collaboration goes, what do you think opened you up to trying something that is such a departure from your previous work?

VINCENT: It’s true, I don’t usually shoot human subjects, and when I do I tend to avoid capturing the face. The face and also hands are especially powerful conduits of emotion, and it’s rather easy to find yourself falling into the trap of capturing overly contrived gestures and expressions.

For our collaboration, I wanted to reconcile my interest in more formal elements of photography with portraiture. I also wanted to explore my love for all things kitsch. What could be kitschier than bringing back glam rock? And then there’s also the queer element that I felt we could explore together. That’s an aspect of my identity that I haven’t really addressed in my work thus far.

JASON: Queerness has definitely been a prevalent feature in my work. Many of the individuals that I shoot are queer and/or gender non-conforming.

VINCENT: You’re shooting your life and your friends. I like that authenticity, even if I think that’s a gross word, but you know.

JASON: [Laughs] Well, I’d actually like to draw a distinction between my work that involves shooting my friends—the more candid stuff—and my planned/posed work, which is more contrived to use a word you mentioned earlier. The “authenticity” of my candid work does contrast with the more editorial-style shoots that I’ve done.

VINCENT: That’s true, but at the same time I feel like staging and direction don’t necessarily make something inauthentic or contrived. Take cinema, for example: the whole craft itself is artificial in nature, but it’s in the service of conveying some sort of truth. That’s always there even in your staged photos.

JASON: I suppose you’re right. They might just be different approaches to capturing truth.

Growing up in Hawai‘i, we’re surrounded by kitsch. It shapes the way we see our ‘world’ here.

Vincent Bercasio

VINCENT: Going back to queerness as a feature of your work: Would you say that you’re trying to make a point with capturing queerness, or is it just another element of who you are?

JASON: The latter rings truer, for me. Some of my work is queer, but it’s never to make a political statement or anything. I would never try to tell people that there’s a certain way to be queer. So, no, I don’t think I’m trying to make a point out of it.

VINCENT: What about gender roles? Perhaps the way you shoot women is different from the way you shoot men or non-binary individuals.

JASON: Well, my gaze is different depending on who I shoot. So, yes, I suppose I do shoot men and women and non-binary people differently. The process is the result of a different gaze. I mean, if I said I shot everyone in the same way, that’s just like saying that I’m “gender-blind.” And I know that’s not the case.

VINCENT: I get that. It’s not something that I consider often, but my attraction to men probably colors my work in ways I’m not even aware of.

VINCENT: On another note, I also really admire your nightlife work. As a DJ and a photographer, you have a unique insight into the local queer/party scene.

JASON: Well, I’ve been partying for a long time! And I’ve been around party photography for many, many years ever since I lived in NYC in the mid-’00s. Engaging myself with that particular genre of photography was hardly a stretch for me. Being surrounded by super interesting people doesn’t hurt either.

VINCENT: I know that your primary trade is teaching. Would you consider Jason the Teacher all that different from Jason the Artist?

JASON: My teaching practice and my photographic practice all come from the same creative place. The creativity that I use as a teacher is the same creativity that I draw from as a photographer or musician or DJ, et cetera.

Aside from teaching—which I must do because it’s my job—I only engage with my creative outlets when I feel like it. I used to want to pursue being an artist or musician or DJ as my livelihood, but that idea doesn’t seem personally appealing to me today. I’ve found my calling as an educator first and foremost.

I know you dislike when I call myself a photo hobbyist, but I really do think that I am. I am serious about photography, but it is just a hobby for me. For me, it’s like an itch, and I only scratch if I’ve been bitten. Otherwise, I don’t need to. I can let any of my creative practices become dormant until that itch finally reappears. And that’s what I like about not doing it as a job. It’s not an obligation for me. It’s not something that I must do. It’s something I do because I choose to do it.

VINCENT: I guess I have serious itches then [laughs]. I generally agree, though. Doing this for a living sounds appealing on paper, but I really would rather not devote my creative energy into work that doesn’t inspire me. For photography, that itch is wanting to find a quiet moment. There’s all these little grace notes around us that deserve another glance

JASON: I definitely get that from your work. The quietness. There’s not a lot of commotion. You’re capturing things that we all see, but it’s very discreet. Almost like you’re capturing a secret.

VINCENT: Would you say your work is “loud” in comparison?

JASON: Sometimes, but I wouldn’t say that’s always the case.

VINCENT: Does that energy reflect in your shooting style?

JASON: Well, I’m definitely a slower shooter than you. One reason is that I primarily shoot film and you primarily shoot digital. I have a limited number of frames, and it’s painful to think that I’m wasting a shot. Usually, I’m trying to think of what’s next or not to panic if I don’t know the answer to that question. Also, I get a rush when I sense I’m going to get something good, and alternatively, feeling very critical of myself when that doesn’t happen quickly enough. It’s very emotion driven.

VINCENT: It’s interesting that you say you’re critical of yourself in the midst of shooting. I don’t think about what I’m doing in the moment. It’s like reviewing your photos while you’re shooting. They break the rhythm

JASON: That’s one of the best advantages of film, not being able to look at it.

VINCENT: Just doing so for even a second messes up my headspace!

JASON: I’d like to know where you would like to take your photography? We talked earlier about the purpose of queerness in my work. How about you?

VINCENT: I haven’t really been outwardly political in my work. When someone sets out to be political in their work there is that danger of being too didactic, which can have a place in art, but I believe the most interesting connections are made when the viewer is allowed to draw their own conclusions.

JASON: I feel the same way.

VINCENT: One thing that I am interested in is pop/lowbrow culture and kitsch. Growing up in Hawai‘i, we’re surrounded by kitsch. It shapes the way we see our “world” here, this land, Hawaiian culture, et cetera

JASON: Oh yeah, definitely. That kitsch is embedded in our surroundings. Any photograph in Hawai‘i doesn’t have to try to evoke a sense of place. It’s already present.

VINCENT: I haven’t really tried to create a sense of place in my pictures for that reason. It’s incorrect to conflate Hawai‘i with the Hawai‘i that has been sold to outsiders, but when so much has been commodified and plasticized, it’s difficult to find a fresh angle. It’s a landscape of kitsch. Taking pictures here can feel as stale as shooting a sunset. At the same time, it’s possible to think about these symbols in a subversive way, which is what I’d like to explore moving forward.

JASON: Watching you shoot, your direction is very clear on set. It’s really marvelous to watch. You seem to know exactly what to say, and I see you experimenting in real time, but it looks like that process happens in your head quickly and you just try it out in real time

I would never try to tell people that there’s a certain way to be queer.

Jason Chu

VINCENT: When I’m working with people, what I’m more concerned about, beyond the images, is if the subject is responding to what I’m saying. They don’t want to see a hesitant director. Although, sometimes I can be a little too open about how I’m feeling. I’m like, “Oh, that was shitty,” or, “Ew, nevermind.” And I feel bad because at those times, I’m thinking about the picture more than the subject! But I want to make the subject not think about themselves. How do I make them forget themselves?

JASON: Such a director’s statement: “You have to be the character; you are not yourself.” [Laughs] I admire the speed at which you shoot and your self-assuredness. I am probably a little hesitant while shooting, unfortunately. I second-guess myself a lot. So, maybe “critical” wasn’t the best word to describe how I feel during shooting. The self-criticism actually comes right when I get my processed film back.

VINCENT: Oh, that’s the worst feeling ever. That’s why I like digital because the immediacy is so much more comforting. With film, it’s like I have to wait three days to be disappointed.

JASON: [Laughs] I can’t count the number of times I’ve shown you a fresh roll and been like, “This is all crap!” But that’s exactly the feeling I often have, for better or for worse.

VINCENT: At the same time, the fact that there is a limited number of frames keeps you sharp and considerate. I’ve always admired that aspect of film. This isn’t a new observation, but photography is produced and consumed so quickly now for a media forum that isn’t necessarily designed for thoughtful reflection. Film permits us a little more time to meditate, not only on what we’re creating images of and why, but how we disseminate them.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.