In the realm of LGBTQI+ spaces, where representation still falls short, Adam Nathaniel Furman rises to reclaim the overlooked havens designed and cherished by queer individuals.

Words by Niccolo Brandon Serratt

Images courtesy of Adam Nathaniel Furman

When “Queer Spaces: An Atlas of LGBTQ+ Places and Stories” was published in 2022, Adam Nathaniel Furman (they/them) had one goal in mind: for the tome to serve as a beacon, offering historical narratives of queer spaces, shield students from scathing critiques—an experience all too familiar to him—and to bring global attention to these sanctuaries.

In short, they wanted to put a spotlight on unsung pillars of our community that, regrettably, rarely receive the recognition they so deserve.

Through Adam’s invaluable work, the world’s eyes have been opened to the Trans Memorial and Archive in Buenos Aires and the Black Lesbian and Gay Centre in London.

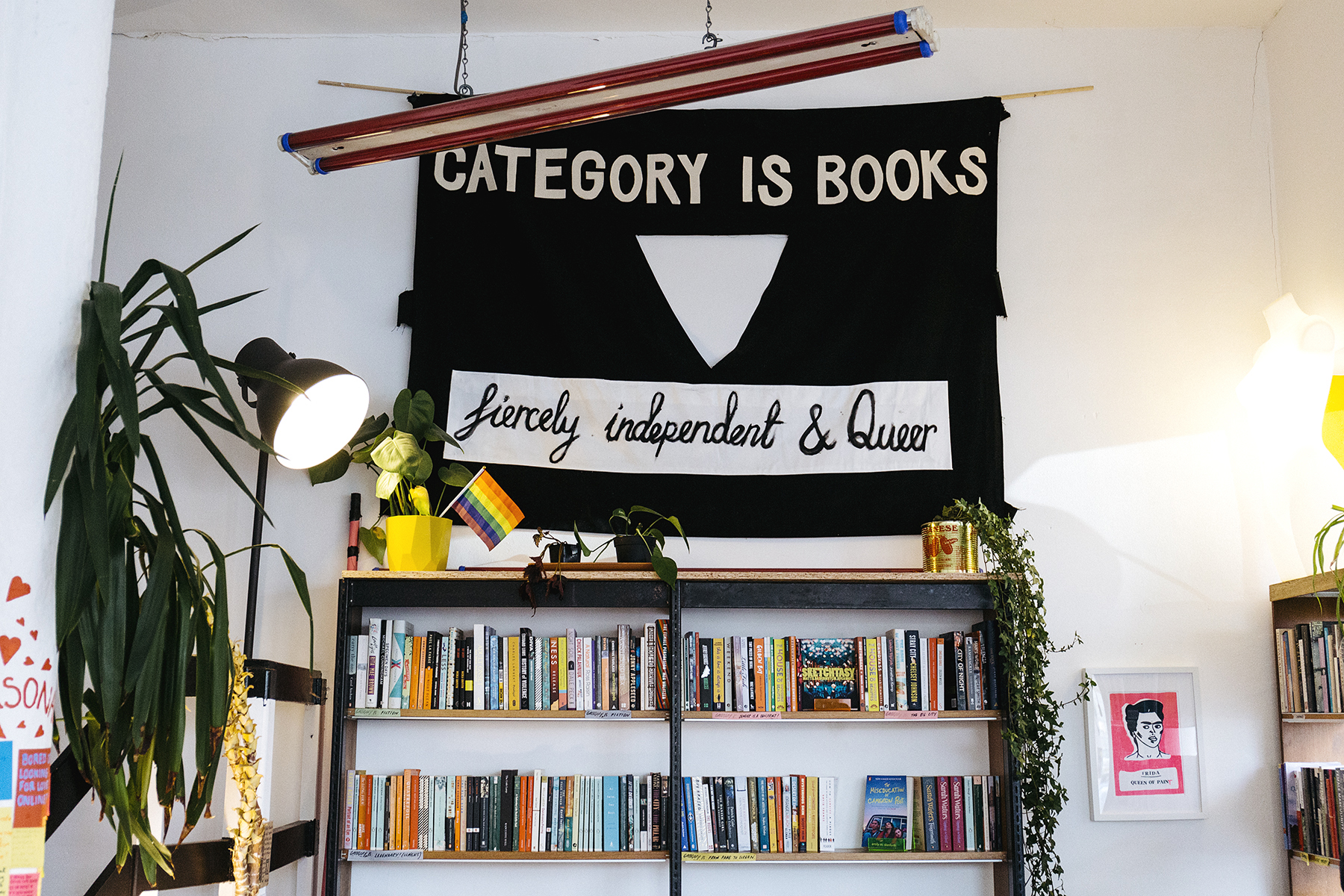

There’s also one of the first gay bars in Tokyo’s Shinjuku Ni-chome; a crumbling cathedral in Managua that’s a sanctuary for the local queer community; an independent bookshop in Glasgow; and ice cream parlour in Havana, “where strawberry is the queerest choice.”

“The personal drive behind my focus on ‘Queer Spaces’ emerges from my own lived experiences,” says Furman, who is of Argentine and Japanese heritage based in London. “As a queer individual studying architecture, expressing my identity through work proved an arduous journey. Those brave enough to incorporate queerness into their architectural projects often faced ridicule and scorn, while many others either abandoned their visions or conformed to societal expectations.”

This book explores the captivating fluidity and ethereal nature of queer spaces, establishing a rich tapestry of references for students and creating a much-needed platform for discussion and understanding.

Adam Nathaniel Furman

Can you give us some background on your journey as an artist and designer?

Adam: I began my artistic journey in 2001 when I studied architecture at St. Martin University, completing a foundation course. After graduating, I ventured into the industry while pursuing my own creative practice until 2016, when I decided to venture out independently. I’ve been involved in various artistic endeavours, including publishing, journalism, art installations, and pavilions. Finding like-minded individuals in my generation was difficult, which compelled me to pave a different path.

What inspired you to focus your work on “Queer Spaces”?

Adam: What struck me was the absence of historical references and examples of queer spaces for students to draw upon when justifying their work. This void left them vulnerable to criticism from their tutors.

In collaboration with fellow passionate individuals, I took it upon myself to co-author a book backed by the esteemed Royal British Institute of Architecture. This book explores the captivating fluidity and ethereal nature of queer spaces, establishing a rich tapestry of references for students and creating a much-needed platform for discussion and understanding.

Could you describe queer spaces in three adjectives that define them?

Adam: “Heirloom” reflects that queer individuals are not automatically born into an established ethnic or cultural group and often must find and form their own culture and community. These spaces help prevent the erasure of older queer individuals’ existence and recognize their valuable contributions to society. “Hope” represents the resilience and determination of the queer community. “Beauty” is a significant aspect of queer spaces, just like the beauty celebrated within queer individuals.

Can you share examples of architectural projects or spaces that have successfully promoted inclusivity and diversity?

Adam: I find inspiration in particular projects that foster a sense of community and acceptance. For instance, the Trans Memory Archive in Buenos Aires is an essential example of passing down knowledge and experiences. This community-driven archive was created by trans people who came together on social media, learning how to raise funds, catalogue, and preserve their history for future generations.

Closer to home is the Black Lesbian and Gay Centre in London exemplifies resilience in the face of adversity. The centre found its space in the railway arches, proving its determination to provide a haven and support for its community, even amidst hostile attitudes.

Queer aesthetics are not limited to a single style but encompass many aspects. Queer spaces arise from the creativity and resourcefulness of queer individuals in specific times and places.

Adam Nathaniel Furman

Could you discuss a specific project related to queer spaces that you’re working on or recently completed?

Adam: One of the projects I’m currently involved in is an exhibition at Kew Gardens scheduled for autumn. It explores the concept of “Queer Botanicas,” and delves into the fascinating queer aspects found in the biology of flowers. In addition, I’m about to launch a permanent art piece called “Kick Your Heels Three Times” on the Norman Foster Bridge connecting One Canada Square to the Elizabeth line train station in Canary Wharf. This artwork features a barcode of colours that represents the diverse and inclusive reality of the queer community.

Are there any misconceptions or misunderstandings you often encounter when discussing the concept of queer spaces, and how do you address them?

Adam: One common misconception is that people often equate queer spaces with a particular style. Some ask if a “queer building” has specific aesthetic features. While it may seem amusing initially, it can sometimes be frustrating. Queer aesthetics are not limited to a single style but encompass many aspects. Queer spaces arise from the creativity and resourcefulness of queer individuals in specific times and places rather than conforming to predefined formal tendencies.

The assumption that queer spaces are solely related to sexual activities or are sexually explicit annoys me. This is an outdated and harmful stereotype. Queer spaces represent inclusive and welcoming environments where all aspects of queer identity are celebrated.

How do you envision your works on queer spaces contributing to the broader conversation around LGBTQ+ rights and representation in society?

Adam: My works on queer spaces aim to empower queer architects, creatives, and individuals by offering historical references and representations. My book, “Queer Spaces,” has been successful, reaching a broader audience. It presents queer spaces in a relatable and accessible manner, challenging misconceptions and promoting understanding. I believe that creating visibility for queer spaces will foster more appreciation for the resilience and creativity of the queer community, countering negative portrayals often seen in the media.

Are any specific places significant to the queer community you love?

Adam: The intention behind my book is to demonstrate that queer history exists everywhere. However, I have a personal affinity for the queer history and community in Central and South America. Sadly, Western writers often overlooked the histories of these vibrant and colourful communities. These regions boast rich queer cultures, especially in cities like Buenos Aires and Mexico City, where artists thrived, thanks to their size and a developed middle class that allowed for the flourishing of queer expression.

Follow Adam Nathaniel Furman on Instagram.